asmjit::x86::Assembler Class Reference [¶]

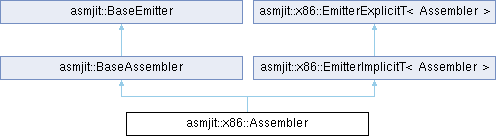

X86/X64 assembler implementation.

x86::Assembler is a code emitter that emits machine code directly into the CodeBuffer. The assembler is capable of targeting both 32-bit and 64-bit instruction sets, the instruction set can be configured through CodeHolder.

Basics

The following example shows a basic use of x86::Assembler, how to generate a function that works in both 32-bit and 64-bit modes, and how to connect JitRuntime, CodeHolder, and x86::Assembler.

The example should be self-explanatory. It shows how to work with labels, how to use operands, and how to emit instructions that can use different registers based on runtime selection. It implements 32-bit CDECL, WIN64, and SysV64 calling conventions and will work on most X86/X64 environments.

Although functions prologs / epilogs can be implemented manually, AsmJit provides utilities that can be used to create function prologs and epilogs automatically, see Function for more details.

Instruction Validation

Assembler prefers speed over strictness by default. The implementation checks the type of operands and fails if the signature of types is invalid, however, it does only basic checks regarding registers and their groups used in instructions. It's possible to pass operands that don't form any valid signature to the implementation and succeed. This is usually not a problem as Assembler provides typed API so operand types are normally checked by C++ compiler at compile time, however, Assembler is fully dynamic and its emit() function can be called with any instruction id, options, and operands. Moreover, it's also possible to form instructions that will be accepted by the typed API, for example by calling mov(x86::eax, x86::al) - the C++ compiler won't see a problem as both EAX and AL are Gp registers.

To help with common mistakes AsmJit allows to activate instruction validation. This feature instruments the Assembler to call InstAPI::validate() before it attempts to encode any instruction.

The example below illustrates how validation can be turned on:

Native Registers

All emitters provide functions to construct machine-size registers depending on the target. This feature is for users that want to write code targeting both 32-bit and 64-bit architectures at the same time. In AsmJit terminology such registers have prefix z, so for example on X86 architecture the following native registers are provided:

zax- mapped to eithereaxorraxzbx- mapped to eitherebxorrbxzcx- mapped to eitherecxorrcxzdx- mapped to eitheredxorrdxzsp- mapped to eitheresporrspzbp- mapped to eitherebporrbpzsi- mapped to eitheresiorrsizdi- mapped to eitherediorrdi

They are accessible through x86::Assembler, x86::Builder, and x86::Compiler. The example below illustrates how to use this feature:

The example just returns 0, but the function generated contains a standard prolog and epilog sequence and the function itself reserves 32 bytes of local stack. The advantage is clear - a single code-base can handle multiple targets easily. If you want to create a register of native size dynamically by specifying its id it's also possible:

Data Embedding

x86::Assembler extends the standard BaseAssembler with X86/X64 specific conventions that are often used by assemblers to embed data next to the code. The following functions can be used to embed data:

- BaseAssembler::embed_int8() - embeds int8_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_uint8() - embeds uint8_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_int16() - embeds int16_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_uint16() - embeds uint16_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_int32() - embeds int32_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_uint32() - embeds uint32_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_int64() - embeds int64_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_uint64() - embeds uint64_t (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_float() - embeds float (portable naming).

- BaseAssembler::embed_double() - embeds double (portable naming).

- x86::Assembler::db() - embeds byte (8 bits) (x86 naming).

- x86::Assembler::dw() - embeds word (16 bits) (x86 naming).

- x86::Assembler::dd() - embeds dword (32 bits) (x86 naming).

- x86::Assembler::dq() - embeds qword (64 bits) (x86 naming).

The following example illustrates how embed works:

Sometimes it's required to read the data that is embedded after code, for example. This can be done through Label as shown below:

Label Embedding

It's also possible to embed labels. In general AsmJit provides the following options:

- BaseEmitter::embed_label() - Embeds absolute address of a label. This is target dependent and would embed either 32-bit or 64-bit data that embeds absolute label address. This kind of embedding cannot be used in a position independent code.

- BaseEmitter::embed_label_delta() - Embeds a difference between two labels. The size of the difference can be specified so it's possible to embed 8-bit, 16-bit, 32-bit, and 64-bit difference, which is sufficient for most purposes.

The following example demonstrates how to embed labels and their differences:

Using FuncFrame and FuncDetail with x86::Assembler

The example below demonstrates how FuncFrame and FuncDetail can be used together with x86::Assembler to generate a function that will use platform dependent calling conventions automatically depending on the target:

Using x86::Assembler as Code-Patcher

This is an advanced topic that is sometimes unavoidable. AsmJit by default appends machine code it generates into a CodeBuffer, however, it also allows to set the offset in CodeBuffer explicitly and to overwrite its content. This technique is extremely dangerous as X86 instructions have variable length (see below), so you should in general only patch code to change instruction's immediate values or some other details not known the at a time the instruction was emitted. A typical scenario that requires code-patching is when you start emitting function and you don't know how much stack you want to reserve for it.

Before we go further it's important to introduce instruction options, because they can help with code-patching (and not only patching, but that will be explained in AVX-512 section):

- Many general-purpose instructions (especially arithmetic ones) on X86 have multiple encodings - in AsmJit this is usually called 'short form' and 'long form'.

- AsmJit always tries to use 'short form' as it makes the resulting machine-code smaller, which is always good - this decision is used by majority of assemblers out there.

- AsmJit allows to override the default decision by using

short_()andlong_()instruction options to force short or long form, respectively. The most useful islong_()as it basically forces AsmJit to always emit the longest form. Theshort_()is not that useful as it's automatic (except jumps to non-bound labels). Note that the underscore after each function name avoids collision with built-in C++ types.

To illustrate what short form and long form means in binary let's assume we want to emit "add esp, 16" instruction, which has two possible binary encodings:

83C410- This is a short form akashort add esp, 16- You can see opcode byte (0x8C), MOD/RM byte (0xC4) and an 8-bit immediate value representing16.81C410000000- This is a long form akalong add esp, 16- You can see a different opcode byte (0x81), the same Mod/RM byte (0xC4) and a 32-bit immediate in little-endian representing16.

It should be obvious that patching an existing instruction into an instruction having a different size may create various problems. So it's recommended to be careful and to only patch instructions into instructions having the same size. The example below demonstrates how instruction options can be used to guarantee the size of an instruction by forcing the assembler to use long-form encoding:

If you run the example it will just work, because both instructions have the same size. As an experiment you can try removing long_() form to see what happens when wrong code is generated.

Code Patching and REX Prefix

In 64-bit mode there is one more thing to worry about when patching code: REX prefix. It's a single byte prefix designed to address registers with ids from 9 to 15 and to override the default width of operation from 32 to 64 bits. AsmJit, like other assemblers, only emits REX prefix when it's necessary. If the patched code only changes the immediate value as shown in the previous example then there is nothing to worry about as it doesn't change the logic behind emitting REX prefix, however, if the patched code changes register id or overrides the operation width then it's important to take care of REX prefix as well.

AsmJit contains another instruction option that controls (forces) REX prefix - rex(). If you use it the instruction emitted will always use REX prefix even when it's encodable without it. The following list contains some instructions and their binary representations to illustrate when it's emitted:

__83C410-add esp, 16- 32-bit operation in 64-bit mode doesn't require REX prefix.4083C410-rex add esp, 16- 32-bit operation in 64-bit mode with forced REX prefix (0x40).4883C410-add rsp, 16- 64-bit operation in 64-bit mode requires REX prefix (0x48).4183C410-add r12d, 16- 32-bit operation in 64-bit mode using R12D requires REX prefix (0x41).4983C410-add r12, 16- 64-bit operation in 64-bit mode using R12 requires REX prefix (0x49).

More Prefixes

X86 architecture is known for its prefixes. AsmJit supports all prefixes that can affect how the instruction is encoded:

It's important to understand that prefixes are part of instruction options. When a member function that involves adding a prefix is called the prefix is combined with existing instruction options, which will affect the next instruction generated.

Generating AVX512 Code

x86::Assembler can generate AVX512+ code including the use of opmask registers. Opmask can be specified through x86::Assembler::k() function, which stores it as an extra register, which will be used by the next instruction. AsmJit uses such concept for manipulating instruction options as well.

The following AVX512 features are supported:

- Opmask selector {k} and zeroing {z}.

- Rounding modes {rn|rd|ru|rz} and suppress-all-exceptions {sae} option.

- AVX512 broadcasts {1toN}.

The following example demonstrates how AVX512 features can be used: